When a remarkable face-altering app — uncreatively titled Faceapp — exploded onto the scene in 2017, it provoked a predicable arc. The app uses the Artificial Intelligence technology behind deepfakes to make mind-bending alterations to a person’s face in near real-time, using only a selfie as input.

Initially, there was fascination. Any celebrity you could name — as well as all your coworkers and extended family members — were suddenly using it to post altered photos of themselves on Instagram, with fake tattoos, artificial sunglasses, and the like.

Next came disgust, when the app started making some truly yucky choices. A “beautify” filter made the faces of people of color look whiter, and the developers followed this up with an ill-conceived feature that let you transform yourself into someone of a different race. Critics called it a virtual blackface. The Faceapp team later apologized on both counts, as well they should.

Finally, the world moved on to fear, with the revelation that the app could be sending your photos to nefarious Russian hackers (spoiler alert: it’s probably not).

As the fervor over the app has died down, though, there has been a renewed interest in its power. Some features are silly (do I need to know what I would look like bright, glossy makeup?), but others are actually quite compelling, useful, and remarkably well developed.

Seeing Your Future

One example of Faceapp’s power is its ability to artificially age a photo. Users can upload a selfie, and see how they’ll look decades into the future. This has a variety of uses, beyond simple vanity.

In medicine, studies have shown that presenting a patient with an aged version of their own face can help motivate them to quit smoking, exercise more, and engage in a variety of healthy behaviors. The thinking is that young people who see a 70-year-old version of themselves are motivated to take care of their bodies now — either to protect that future person or to avoid aging faster than they have to.

Likewise, in personal finance, seeing an aged version of yourself is a good way to spur more retirement savings. Investment company Merrill Lynch started offering this service, which they dubbed “Face Retirement”, to their Millennial-generation brokerage customers. The service presented these clients with an artificially aged photo of themselves at retirement age and then suggested that they contribute to their IRA or 401k.

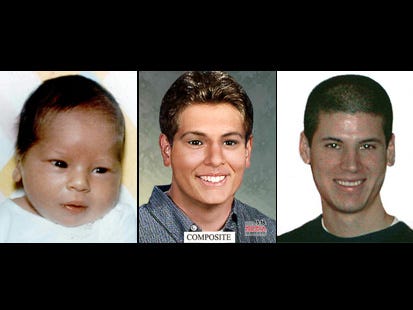

And in policing, artificially aging photos can be incredibly valuable. When children or young people go missing, authorities continue searching for them, often years later. After a decade or more, original photos of the missing person no longer reflect what they’d look like if they’re found.

Aric Austin, for example, was kidnapped at 2 months old. He was found at age 22 and reunited with his mother, based on an aged composite created by the NCMEC (you can read more about their work and support them here).

Currently, police departments employ a painstaking, manual process to age photos. It requires obtaining photos of other family members, analyzing the facial structure of the missing person, making projections about patterns of aging for the person’s population group, and then having an artist manually create an aged version of the person’s face. An Artificial Intelligence solution would make this task much easier and less costly.

Ground Truth

Could Faceapp be this solution? Are its aged photos just playthings, good for a laugh or to poke fun at a friend, but of little value outside an ephemeral Instagram post? Or are they accurate enough for use in medicine, finance, policing and other fields?

To find out, I decided to get some ground truth data. In AI, ground truth data is actual data from the real world — not something generated by a model. It’s used to keep AI systems honest, checking their inferred output against real-world examples to see where they’re accurate and where their models of the world fail.

We’ve all seen articles that try to do this with Faceapp and celebrities — here’s Judi Dench as a teenager, here’s the Faceapp aged version of her teenage photo, and here’s what she really looks like today. They’re fun to read, but do they capture the app’s true capabilities?

Celebs are Problematic

There are a couple of problems with this approach. One is that Faceapp was trained on photos of celebrities. This makes it likely that for any given celebrity childhood photo you feed into the model, the app already knows — somewhere in the depths of its neural networks — what that person actually looks like today. It’s still altering their face, but it’s starting with an advantage since in many cases, it has a current photo already and thus knows the answer in advance.

Another problem is selection bias. There are lots of photos of celebrities out there. If you’re a journalist doing a piece about Faceapp, you’ll likely run a photo of a young celeb through the system, age it, and then look for a modern photo showing the same celeb as an actual old person.

Naturally, you’re going to select the modern photo that looks the most like the aged photo you created — no one writes a piece with the aim of saying “Here’s an aged photo, and here’s a photo of the same person today. There are probably photos out there that look more like my aged version, but I chose this one randomly, for the sake of scientific accuracy.”

Instead, you’re going to choose a photo that paints the app’s results in the best possible light. And because you might have 5,000 or more modern photos for a given celeb, it’s very likely you can find one that looks almost exactly like your aged version, even if the majority don’t. It’s not that journalists are being sneaky — it’s just that with celebs, there are so many choices out there that it’s easy to pick a photo that happens to work especially well, and thus inadvertently overstates the app’s results.

If celebs are out, then how can we test the accuracy of Faceapp’s aging algorithm? It’s not like you can run an experiment on yourself — you’d have to take a selfie now, age it with Faceapp, and wait several decades to see how the results measure up. By then, we’ll probably have neural networks embedded in our eyeballs, and apps will be as distant a memory as the telegraph or the dialup modem.

What we’d need is a series of photos of a normal person — taken early in their life, in middle age, and when they’ve become a genuine senior. This would provide at least one piece of valuable ground truth data, to see how Faceapp performs in the real world on real people.

The Solution? My Grandpa

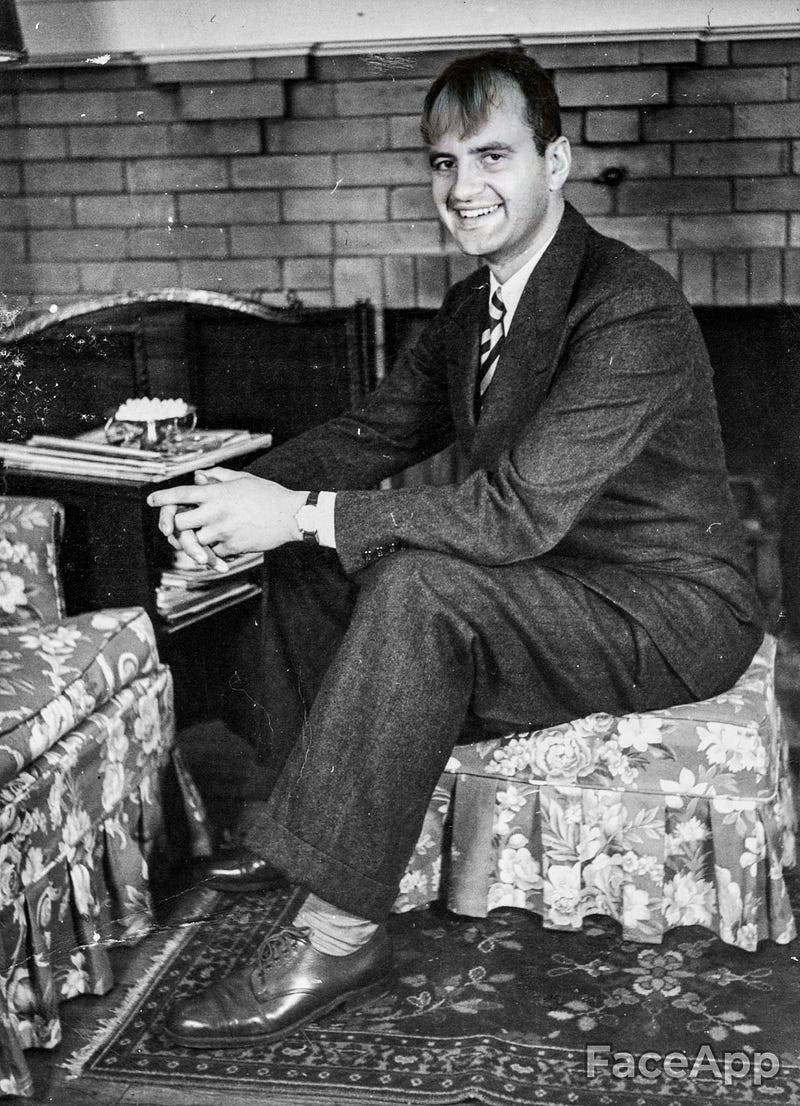

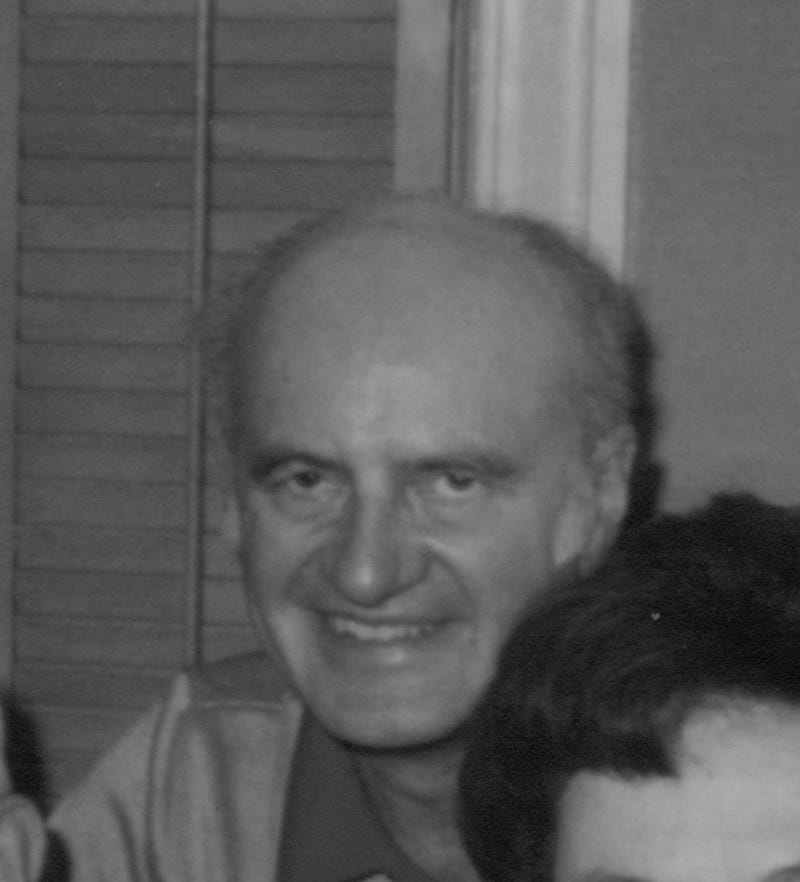

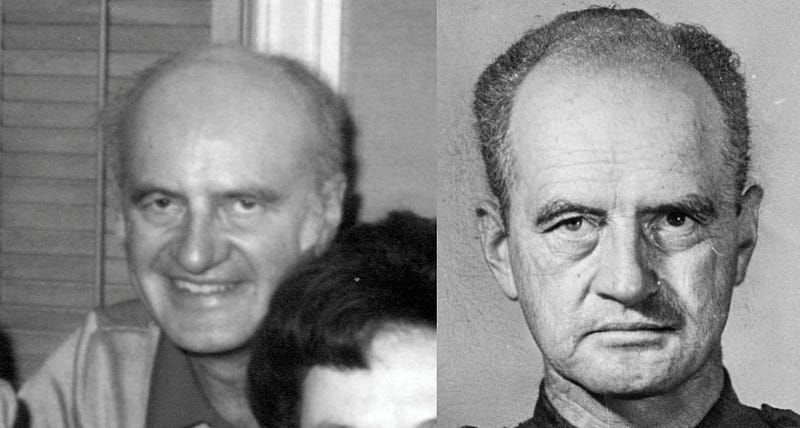

I have a solution — here he is:

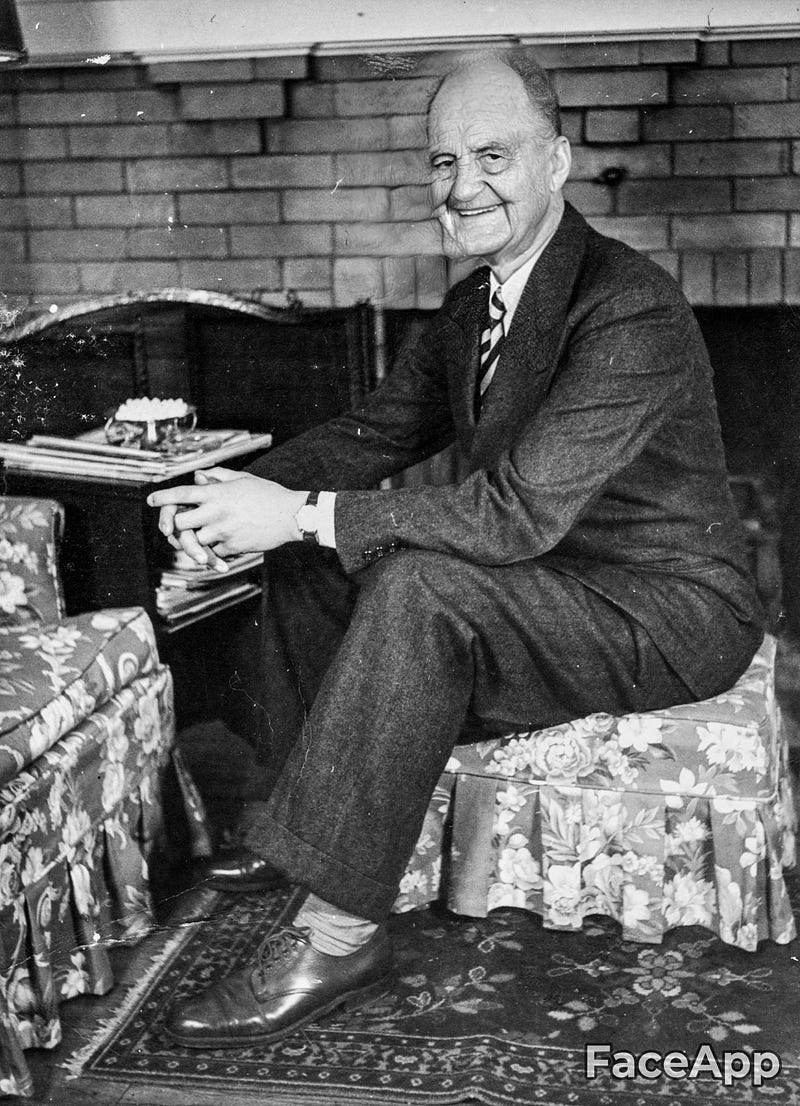

This is my grandpa, Max. He was a great guy. And a good looking dude, too — shown here embodying the look of the suburban 1950s man, with his neat suit and floral-print living room.

This was taken around 1955 when he was in his 30s. That’s a perfect age since many of the people aging their photos with Faceapp are Millennials in their 20s and 30s. But here’s the even more helpful part — I have photos of my grandpa from throughout his life, so we can see how the app performs on aging photos to different future times.

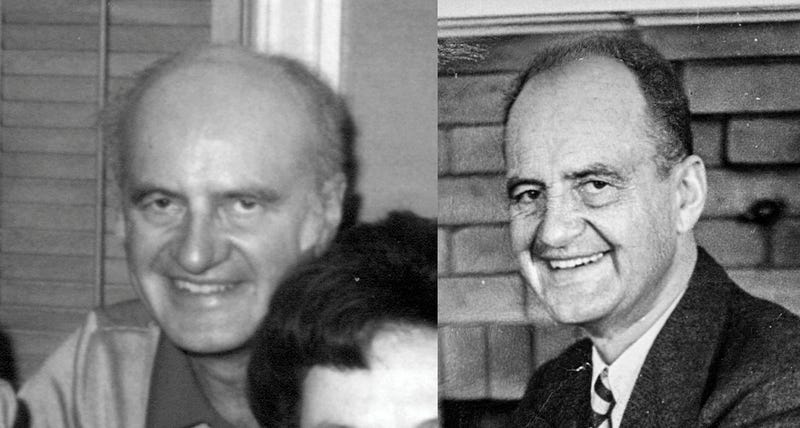

Let’s run his photo through the app, and use the aging feature. The app tends to age people about 20–30 years. Here’s how Faceapp thinks he’d look in his mid-50s.

So far, so good. That looks pretty believable — no weird AI artifacts, misplaced ears, or anything terribly out of the ordinary. It maybe went a little crazy with his forehead— and felt the need to add some wrinkles to the brick fireplace behind him — but overall it’s looking pretty good.

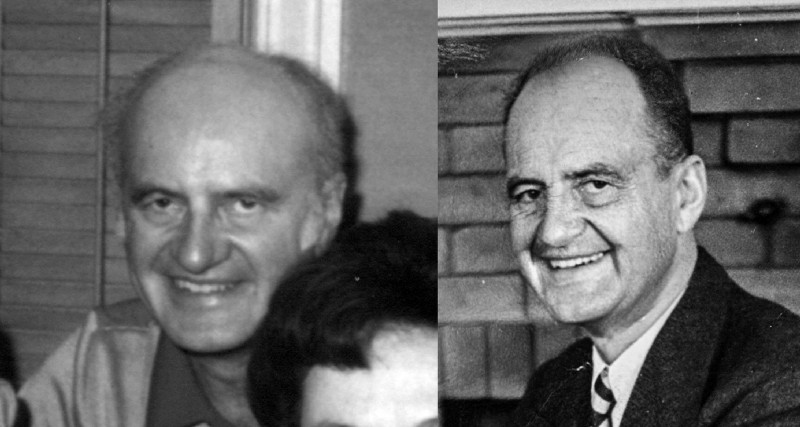

So what did he really look like as an older person? Here’s a photo of him in 1972, when he was around 50.

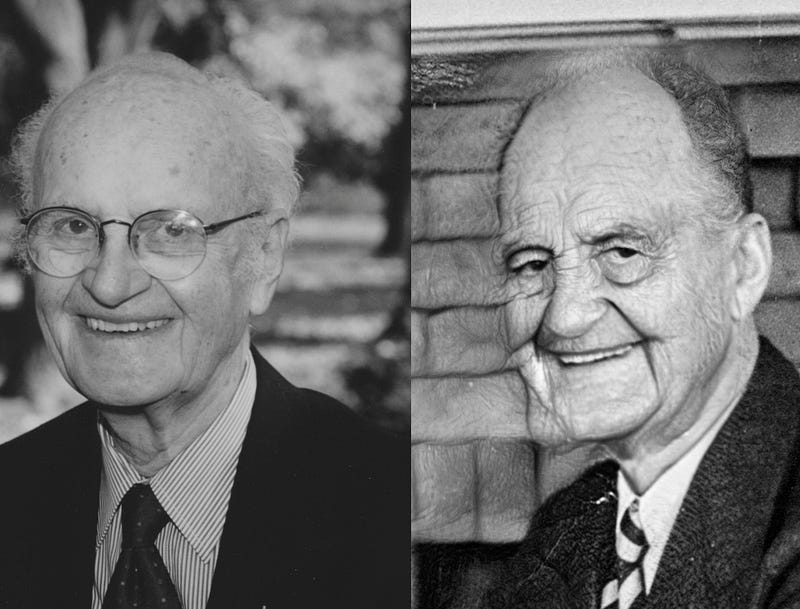

Here are the two faces side by side — the real one on the left, and Faceapp on the right.

There’s some good and some bad here. I think Faceapp did a pretty good job around his eyes, and the nose looks spot-on. The app was more generous than nature when it comes to his hairline (this never held him back in life), but the smile is there, and so is the shape of the skin around his mouth and the bottom portion of his face.

The biggest failure, I think, is in the face shape. Because in the original portrait he is turned to the side, the app made his aged face a little too vertical and pinched together. Viewing him from head-on, as an actual 50-year-old, his facial shape is definitely different.

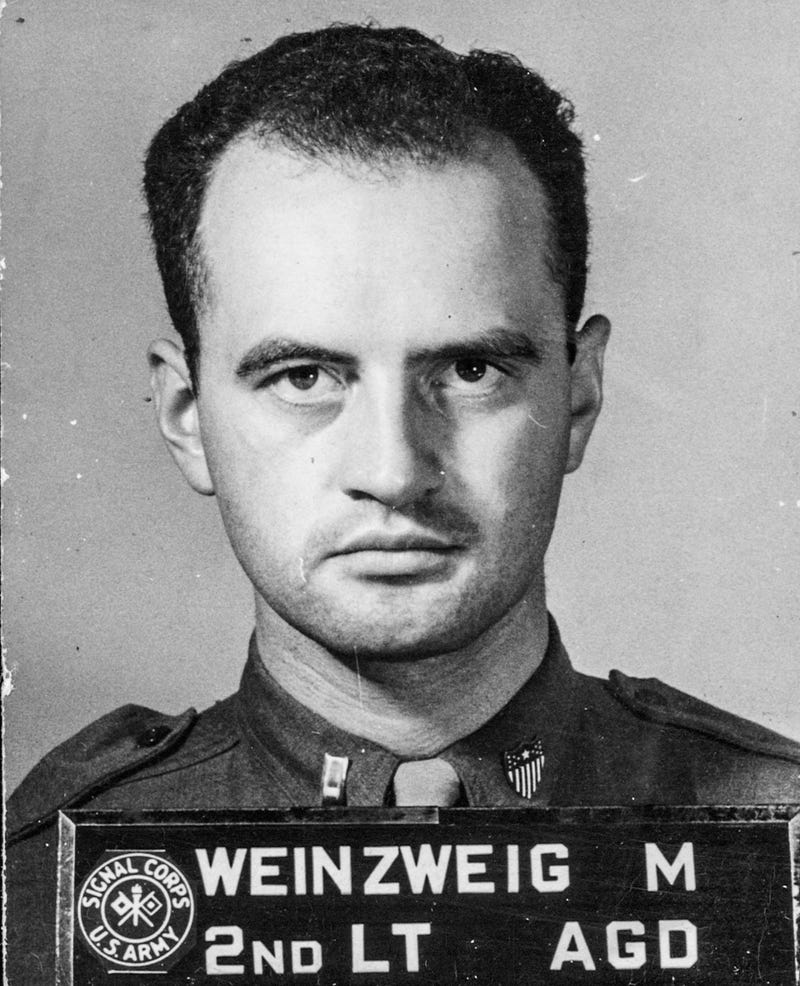

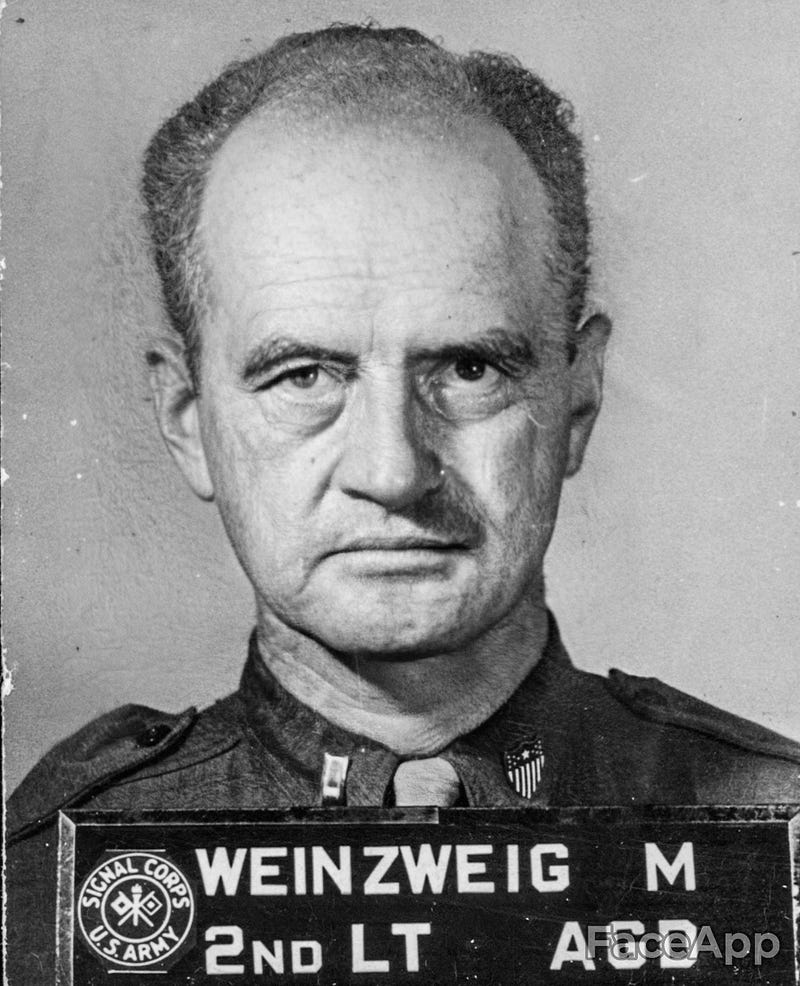

Let’s try again, but with a different photo. This Signal Corps picture from his service in World War 2 (thanks, Grandpa) isn’t the most flattering photographically. But because it’s professionally shot in a studio setting, with a neutral facial expression and the subject looking straight at the camera, it’s the bread and butter of deepfakes — and an almost ideal test case for transformation via AI.

Here’s the aged version.

And side by side.

The facial expressions are different, but I think this gets much closer. Again, it misses on the hairline, but the eyes, mouth line, nose and eyebrows are quite close. And the facial shape is better, though still not perfect. If anything, the real Max had fewer wrinkles than the Faceapp one. But fundamentally, the aged version and the reality look quite similar — especially given that this was generated from a photo shot decades before.

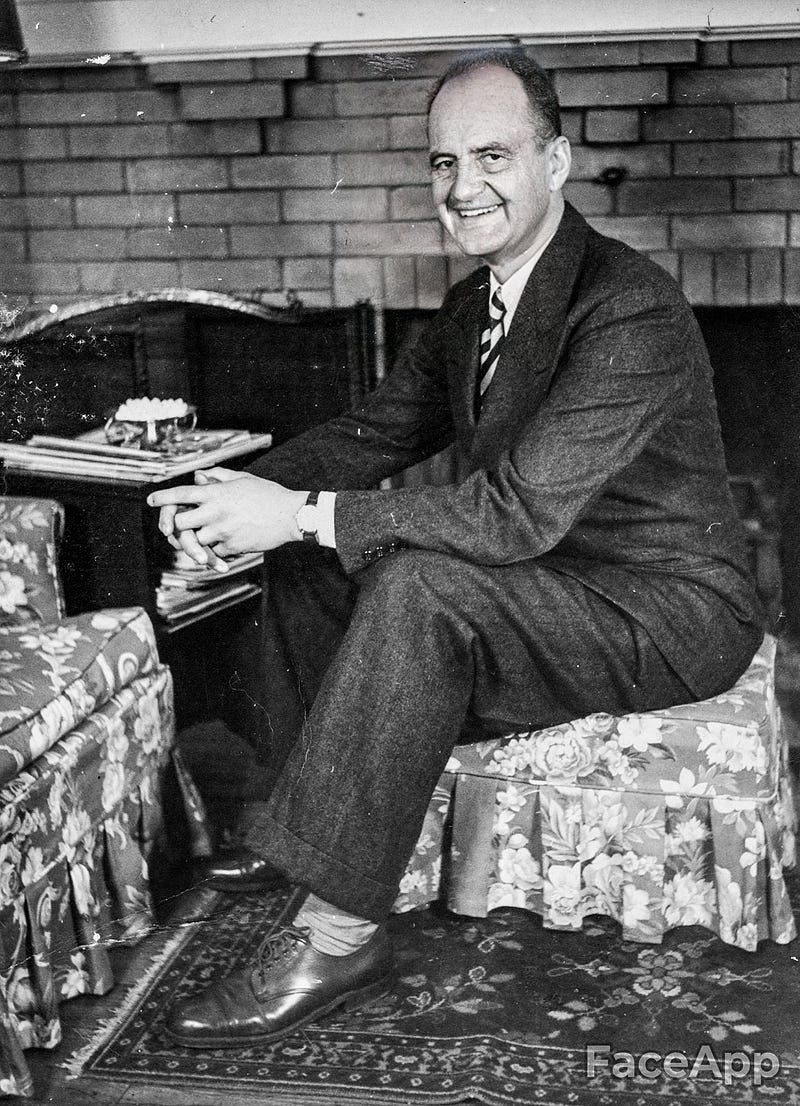

To go even farther, I then ran the first aged photo through the app to age it again, bumping Grandpa up into his 80s. The result is a little funkier looking since the app is artificially aging a photo that’s already been artificially aged. It’s like making a photocopy of a photocopy–you lose fidelity. Still, it’s not bad.

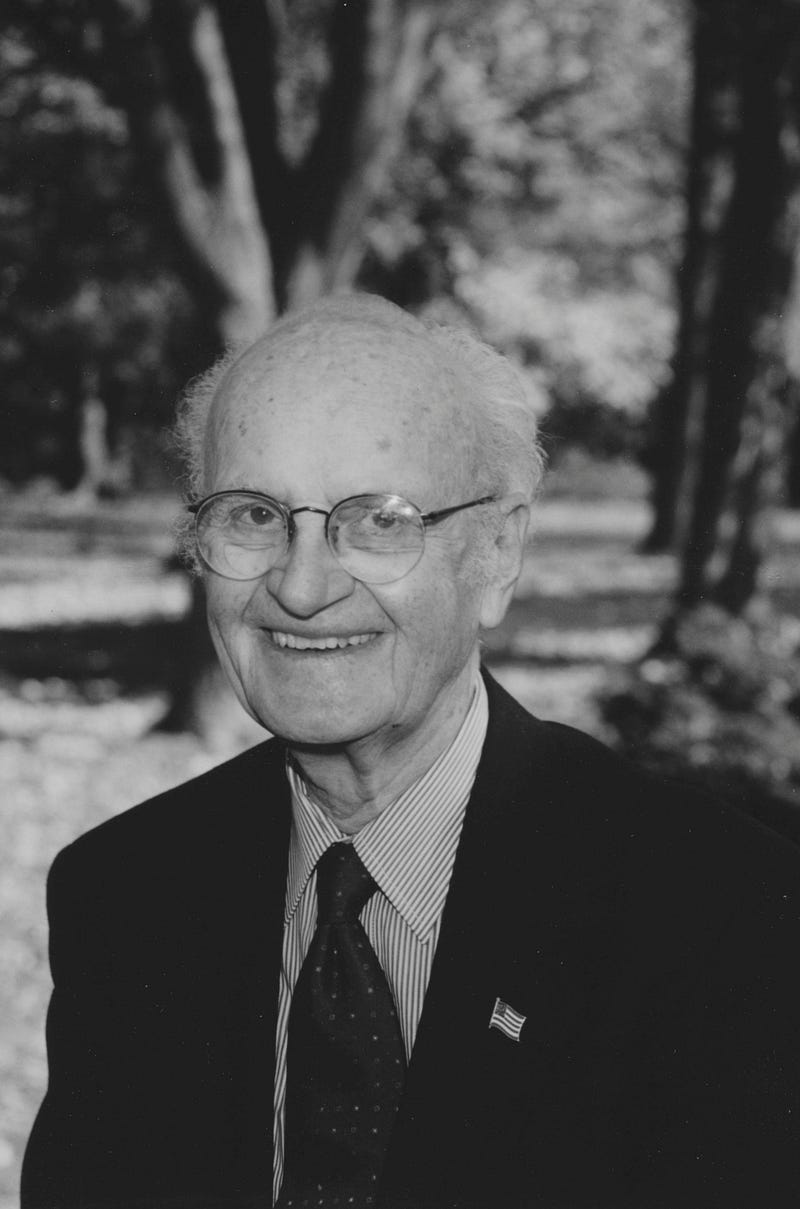

Here’s a photo of him in the early aughts, when he was genuinely around 80 years old, and just a few years before he passed in 2006.

Let’s see them side by side:

I think we can all agree that the real guy is much better looking. But there are still some things the app gets right. Look at the mouth and teeth, for example, or the lines around the nose. The facial shape is still wrong, and the double-aged face has many more weird artifacts, but there’s still a lot of interesting similarities, for something that’s projecting 50 years into the future.

Ready for Prime Time?

So is Faceapp ready for prime time? Based on its performance with my grandpa, could its technologies be applied to mission-critical use cases, like aging photos of a missing person?

I would say it’s a mixed bag. There are some things the app gets right — and remarkably so, given that it’s taking a historical photo and blasting it decades into the future. But there are also some subtleties that it gets wrong. Again, the most significant is the overall facial shape. This changes as we age, and simulating the changes is a harder problem than simulating changes to other facial features, like skin and hair.

Skin gets wrinkly, and hair recedes over time. These kinds of changes can be simulated, and relatively easily plastered onto a current photo to make someone look older. But understanding how facial shape will change with age is more complicated, and requires making literal structural changes to the face itself. This is clearly beyond the capabilities of a basic aging app unless it’s working with a perfectly lit, straight-on photo like the Signal Corps pic — and even then, it’s not perfect.

Still, from these results, it’s clear that Faceapp is more than just a party trick or a plaything. It’s not throwing on some crow’s feat and making up a funny, wrinkly face to post on your Instagram — many of the skin, hair, eye, teeth and other surface-level changes are spot on.

For mission-critical applications, that could make it (or similar tech without the sketchy Russian concerns) a useful feature for creating the first draft of an aged face. A human expert could then edit the face, adding in their own knowledge about the deeper changes associated with aging, like changes to bone structure.

But for less mission-critical applications — like finance or even the medical example — I’m pretty impressed, and I think the app’s technologies have immediate value today. The aged photos look close enough to the real thing that when I see mine, I’m reasonably confident it could capture how I actually look at 50 or 70. And that’s powerful reassurance — it makes me think that seeing an aged version of myself isn’t just a scare tactic. I might actually look like that one day. Better call up Merrill Lynch and fund the ‘ole IRA.

Tools like Faceapp will likely get better with time. And commercial versions are probably already good enough to be used in police applications.

But let’s not wait. Let’s start using tech like Faceapp and its underlying tech now. Even if you’re not prodding people into quitting smoking, seeing an older version of yourself is a powerful experience — it reminds us of the importance of living in the moment, and valuing every moment of the time we have. Knowing that the aged faces it creates are reasonably accurate — that 20-year-old aging their youthful face now may really look like the 70-year-old the app conjures up — makes that experience all the more powerful and moving.

Still, this is Faceapp we’re talking about. So to conclude, here’s how my grandpa would look with bangs.