“All children are artists,” Picasso famously said. That’s true, but you’re still unlikely to see your toddler painting like Vermeer. When you’re only a year out from realizing that you have hands, it’s hard to paint or draw like a virtuoso, no matter how complex your ideas are.

With today’s advances in generative AI, though, that’s all starting to change. Systems like Dall-E from OpenAI can take in a text prompt and generate a photorealistic image. Websites are already cropping up that sell or share the text prompts required to create useful AI images.

If you want a truly creative Dall-E prompt, though, there’s a better solution than buying one— simply ask a child.

Adults Are Boring

As an AI pro with a Cognitive science degree and 10 years of experience in the field, I’ve served as a Beta tester for OpenAI for several years. That means I got access to both GPT-3 and Dall-E before nearly anyone else.

I’m also a father of three kids five and under. In my early testing, I was blown away by DALL-E’s generative power. The system is capable of generating incredibly realistic images of nearly anything you can imagine.

Unlike alternatives such as Midjourney, it’s also deliberately limited to creating PG images — anything violent, suggestive, or otherwise inappropriate gets blocked.

Within a few days of testing DALL-E, I started wondering what a child would do with the system. I could ask DALL-E to generate photos of anything I wanted, but I felt like my ideas were still constrained by my adult expectations of what a photo or illustration could be.

Many of my generations looked like stock images — useful, but still fundamentally normal and in the same pattern of every other image I’ve seen. Adults, after all, are boring.

To break out of the mold of normalcy, I showed Dall-E to my kids.

Generative AI for Your Two-Year-Old

“This is a cool app that creates a photo of whatever you want it to,” I said to my kids. “What would you like to make?”

I gave them a mundane example, directly from my boring adult brain: “An orange sitting on a table.” DALL-E made the image.

My two-year-old thought about this for a moment. “A monster eating an orange!” he responded. DALL-E obliged.

That felt a little scary, so I turned to something more familiar. “How about your dog?” I said. “If you could see your dog doing anything you wanted, what would it be?”

My two-year-old thought for a moment. Then — riffing on our earlier conversation — his face lit up, and he yelled, “A dog eating an orange!”

We have Bichon Frises, so it was pretty easy to get DALL-E to generate a photo of something that looks — uncannily — like his dog eating an orange.

That’s bizarre and remarkably photorealistic. It’s also something we could never do in reality since whole oranges aren’t exactly good fare for your Bichon.

On another day, my two-year-old was being silly and came up with the idea for a Banana Phone. I asked if he wanted to see one, and of course he liked the idea. We plugged “A person speaking into a banana phone” into DALL-E, and it duly produced exactly that.

Pushing the Boundaries

Next, I presented DALL-E to my five-year-old. Like every kindergartener on the planet, he likes branded characters. One of his first prompts was “Spongebob Squarepants riding a little red wagon to the beach.”

Perhaps to its creators’ chagrin, DALL-E is terrific at ripping off trademarked characters. If something is present in the system’s training data, DALL-E will learn how to draw it. That applies equally to mundane shots of food, vacation photos, and Nickelodeon characters.

The system has even been known to faithfully produce a pretend Getty Images watermark on certain photos with an editorial feel.

Dall-E has no problem honoring my son’s request.

As my five-year-old got more familiar with the system, though, he quickly started to find its limits. DALL-E is great at creating images of discrete objects, but once you begin to connect those objects together in any kind of specific way, the system starts to fall apart.

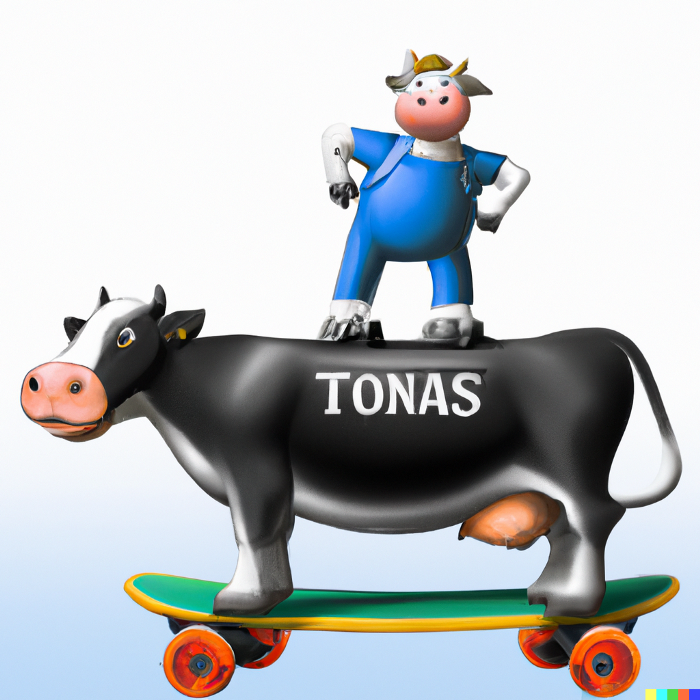

When my son asked for “Thomas the Tank Engine riding a skateboard on top of a giant cow,” DALL-E struggled.

It got some of the basic elements (a skateboard, a cow) but didn’t seem to understand that Thomas the Tank Engine is a single entity (it seems to have named the cow Thomas) and that he was supposed to be riding a skateboard on the cow (here, the cow is riding a skateboard).

This prompt also revealed DALL-E’s struggles with producing specific numbers or text, with “Thomas” becoming “Tonas.” In short order, my son had managed to create a perfect edge case that illustrates many of the ways in which DALL-E currently fails.

Children as Beta Testers

At a recent conference I attended, researcher

Javier Ideami compared today’s generative AI systems to the now-iconic framework that neuroscientist Daniel Kahneman developed to describe the human brain.

In Kahneman’s framework, the brain uses two systems: System 1 is fast and intuitive, and System 2 is conscious, reflective, and detail-oriented. System 1 is responsible for “good enough” tasks like quickly glancing at a picture and understanding its basic contents, whereas System 2 is responsible for tasks that require dedicated, systematic thought, like solving a math problem.

Generative AI systems, Ideami said, are currently all about System 1. They can throw together pixels into a good-enough image of a certain famous resident of a Pineapple Under the Sea, for example, but when it comes to things that require symbolic precision — like producing text, creating images with a specific number of objects, or showing multiple objects in relation to each other — their performance degrades fast.

Because we’re predictable, adults are easier for systems like DALL-E to fool. The kinds of grownup things that I asked the system to produce — the Golden Gate Bridge in the style of Mondrian, a stock photo of a gavel on a blue background — are the kinds of things that it excels at making. They’re images where “good enough” will cut it.

My son’s desire to combine objects, assign names, and otherwise do unpredictable, specific things led him to the system’s edges much faster. Children — because they don’t think like adults — may thus make ideal Beta testers for a system like DALL-E.

Children as Creators

As much as children can probe DALL-E’s boundaries, though, they can also work within the system to produce some delightful creations. As my five-year-old used DALL-E more, his creations started to take on a more bizarre, Dadist twist.

He made things like dogs swinging from chandeliers (we’ve been listening to Sia) and a donkey riding on a train.

He’s also produced some convincing children’s book illustrations of things like dump trucks and car transporters driving in the desert.

At the moment, he needs to dictate his prompts to me, so that I can enter them into the DALL-E interface. Over time, though, I could see the system evolving to the point where its voice recognition was good enough — and its content moderation strong enough — that children could be let loose and allowed to use the system to create things directly.

What they’d make would, I’m certain, be fascinating. Again, my kids already thought way farther outside the box than I did in designing prompts. And the ability to come up with an idea and quickly, magically see it created for them was clearly thrilling.

In time, I wonder how the abilities provided by systems like DALL-E might shape kids’ art. Every parent has had the experience of receiving a crude crayon drawing from their kid, asking what it shows, and getting a profound respond like “all the love in the universe.”

Kids’ minds are clearly far more advanced than their motor skills when it comes to creating art. What if systems like DALL-E could help to bridge the gap? What if these systems could allow kids to imagine absolutely anything — with all the glorious, bizarre creative possibilities that entails — and have it made for them right on the spot?

Picasso was right that every child is an artist. Now, with systems like Dall-e they may finally have the tools to bring their artistic ideas to fruition.